Human Milk Oligosaccharides and Protein in Infant Formula and Health Outcomes

- Here we present highlights from a recent Biostime Nutrition webinar with guest speaker Professor Peter SW Davies. Peter is an Honorary Professor of Childhood Nutrition within the Child Health Research Centre at the University of Queensland and an independent consultant to the food and pharmaceutical industries

Human milk is a dynamic, changing entity and its composition is influenced by short term and longer term factors, such as prematurity and post-natal age, as well as exhibiting significant diurnal changes and variability in composition throughout any individual feed.1 Nevertheless, the literature does contain data that allows broad values for the composition of human milk to be descibed.1 Thus, in term infants, at 3–4 weeks of age breast milk contains, on average 1.5 g/100 ml of protein and 1.6 g/100ml of oligosaccharides.1 Whilst these two components are small percentages of the total, they both have significant roles in health outcomes.

Childhood obesity is associated with significant short- and long-term health problems.2 In 2010, after reviewing data from 450 nationally representative cross-sectional studies from 144 countries, the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimated there were 43 million preschool children who were overweight or obese, with an additional 92 million at risk of being overweight.2 Further they predicted significant increases in those numbers in 2020. For instance, it was suggested that in Africa the number of overweight or obese pre-school children would rise from 13.3 million in 2010, to 22 million in 2020, with an equivalent rise in Asia from 17.7 million to 24.3 million. Whilst the risk of becoming overweight and obese is clearly multifactorial, there is good data to support the idea that protein intake in infancy and childhood, may play a major role in increased adiposity in this population.3

A key consideration here is that human milk is dynamic and whilst there is considerable inter-individual variation, the mean protein content drops rapidly in the first few weeks of lactation.3 Concentrations fall from 1.8 g/100ml in the first week, to around 1.2 g/100ml by 3–4 weeks, then stabilises around 0.9 g/100ml by 10–12 weeks. As infant formula cannot mimic these changes and generally has higher levels of protein than breast milk, formula-fed infants can consume more protein than breast-fed infants over a significant period. Data from the German Dortmund Nutritional and Anthropometric Longitudinally Designed study (DONALD) suggest that the mean difference in protein consumption between breast-fed and formula fed infants at 6 months of age was 6.5 g per day, but much greater differences could be seen at the highest levels of consumption of protein.4

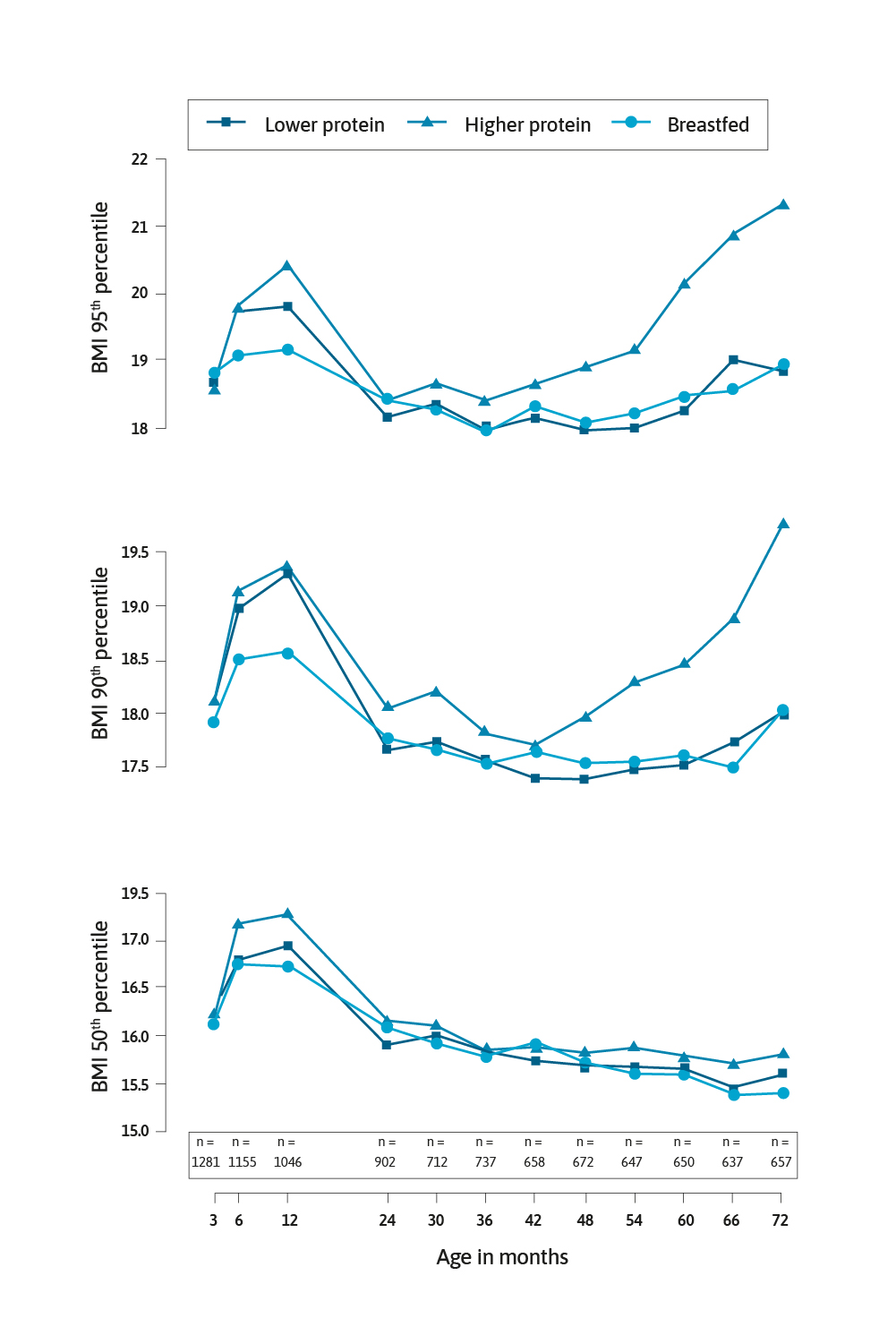

A significant study in this area was the European Childhood Obesity Project.5 This multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) allocated formula-fed infants in the first 8 weeks of life to receive infant formula and follow-on formula with lower (1.77 and 2.2 g protein/100kcal, respectively) and higher (2.9 and 4.4 g protein/100kcal, respectively) protein contents for the first year of life. For comparison, a cohort of exclusively breast-fed infants were also followed. Weber and colleagues reported in 2014, data collected on the infants when they were 6 years of age.6 Crucially the infants who had the high protein formula had a significantly higher body mass index (BMI) by 0.51 kg/m2 (95% CI: 0.13–0.90; P=0.009). The risk of becoming obese in the high protein group was 2.43 (95% CI: 1.12–5.27; p=0.024) times higher than the low protein group.

There have been numerous studies that have demonstrated a relationship between high protein intake in infancy and early childhood and later weight gain, weight status and becoming overweight or obese.3,7-13 Most of these studies used BMI as the primary outcome measure, but importantly some studies have also assessed body composition (fat and fat-free mass).3,10 The physiological mechanism linking high protein intake to becoming overweight or obese has been described as follows, higher protein intake stimulates the secretion of insulin-like growth factor I, consequently cell proliferation leads in turn to accelerated growth and increased adipose tissue.5,7,15,16 Indeed, the evidence linking high protein intake in infancy and later overweight and/or obesity is so strong that the 2012 Australian National Health and Medical Research Council’s Infant Feeding Guidelines stated it is preferable to use formula with a lower protein level.17

These multifunctional glycans are the third most abundant solid component of human milk after lactose and lipids.18 They are made of five basic monosaccharides, namely glucose, galactose, N-Acetylglucosamine, fucose and sialic acid. The different structures seem to influence the functions of the around 150–200 HMOs that have been identified to date. The amounts of HMOs in human milk vary markedly between women with a great deal of inter-individual variation, although the HMO profile of any one individual is much more constant. There are also differing concentrations of HMOs during differing stages of lactation. Colostrum contains around 20–25 g/L of HMOs, whilst the concentration in mature milk is lower at 5–15 g/L.18

There are many factors that affect or drive HMO production by individual women. Notably, an important factor relates to the Lewis system and secretor status.19 Azad and colleagues20 reported, seasonal and parity effects, whilst others have shown important geographic effects,21 and animal studies indicate that diet and exercise changes the amount and profile of HMOs.22

HMOs act as a powerful prebiotic in humans and are digested by potentially beneficial bacteria in the large intestine.23 HMOs also directly influence immune function in many ways. For example, HMOs are known to reduce intestinal crypt cell proliferation, increase barrier function, and inhibit bacterial and viral infections by binding to pathogens in the gut lumen, or by inhibiting binding to cell surface glycan receptors.24 There is burgeoning literature that describes the potential benefits of adding HMOs to infant formula.

Marriage and colleagues25 evaluated the effect on growth and tolerance of infants to a formula supplemented with the HMO 2’ fucosyllactose (2’FL). Two different formulas were tested with identical macronutrient and energy contents, but with the addition of 0.2 g/L or 1.0 g/L of 2’FL. They concluded that there were no significant differences in weight, length and head circumference between the infants who were fed supplemented formula vs the breast-fed control group, for up to 4 months. The supplemented formula was also well tolerated. The possible effect of HMOs added to infant formula on the gut microbiota was the focus of a randomly assigned study reported in 2016.26

This study used two HMOs, 2’FL and lacto-N neotetraose (LNnT), supplemented to formula, then compared the gut microbiota against breast-fed infants at 3 months of age.

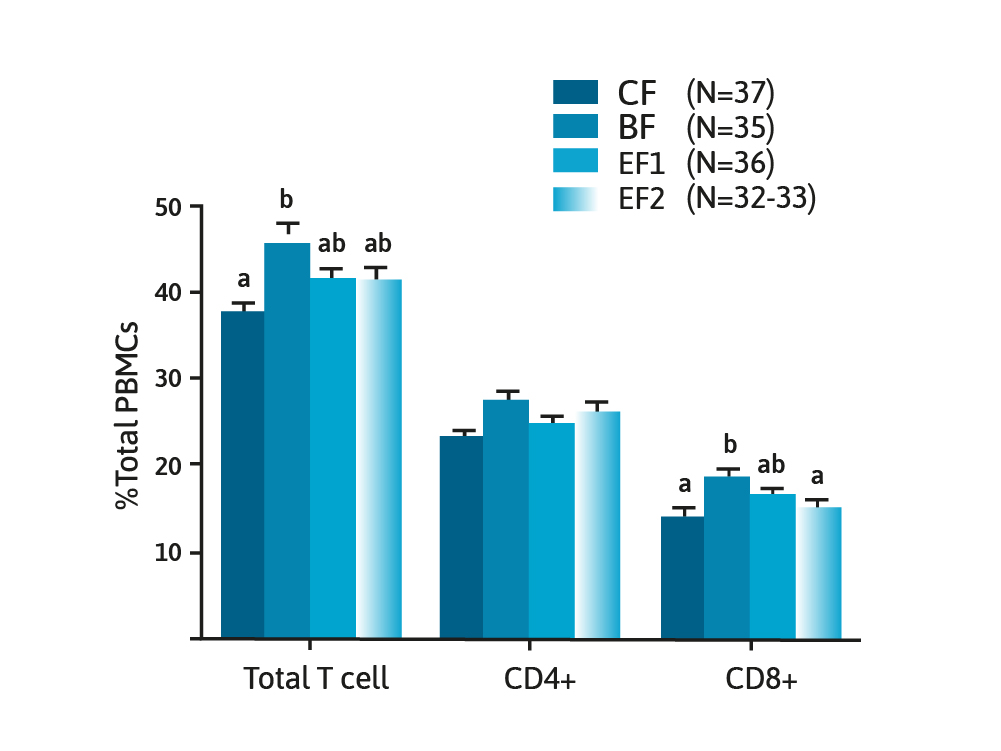

They concluded that at 3 months of age, the microbiota of the HMO supplemented formula-fed infants appeared to be closer to that found in breast-fed infants, when compared to infants consuming formula with no added HMOs. The role HMOs might have on immune function has been previously described24 and evaluated in a RCT of 150 infants allocated to one of three formula consuming groups with varying amounts of 2’FL compared with a breast-fed control group.27 Measurements of immune function were undertaken, and the authors concluded that formula containing a single HMO (2’FL) modified innate and adaptive immune profiles to be more like that of the breast-fed control group.

Other studies with infant formula containing HMOs have examined weight gain, behavioural patterns, digestive tolerance28 and its use in extensively hydrolysed infant formula designed for infants with a cow’s milk protein allergy.29 These studies showed some benefits and/or good tolerance. It is likely that there will more studies in coming years as the addition of HMOs to infant formula becomes approved in more and more countries.

Despite being relatively small components of human milk, both protein and oligosaccharides can have important effects on health in both infancy and childhood. The challenge for scientists and manufacturers of infant formula is to be able to reduce the protein content of formula, within the confines of national and international regulations, and to understand in detail the role of individual HMOs in providing health benefits to infants and children.

- Gidrewicz DA and Fenton TR. BMC Pediatrics 2014;14:216 .

- de Onis M, et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2010;92(2):1257–64 .

- Jen V, et al. Clin Nutr 2019;38(2)1296–1302 .

- Alexy U, et al. Ann Nutr Metab 1999;43:14–22 .

- Koletzko B, et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1836–45 .

- Weber M, et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;99(5)1041–51 .

- Rolland-Cachera MF, et al. Int J Obes 1995;19:573–8 .

- Scaglioni S, et al. Int J Obes 2000;24:777–81 .

- Gunnarsdottir I and Thorsdottir I. Int J Obes 2003;27:1523–7 .

- Gunther ALB, et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:1626–33 .

- Ohlund I, et al. Euro J Clin Nutr 2010;64:138–45 .

- Alexander DD, et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;104: 1083–92 .

- Pimpin L, et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;103:389–97 .

- Inostroza J, et al. JPGN 2014;59(1):70–7 .

- Socha P, et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94: 1776S–84S .

- Rzehak P, et al. Growth Horm IGF Res 2013;23:149–58 .

- NHMRC. 2007 Infant Feeding Guidelines. Canberra. NHMRC .

- Bode L. Glycobiology 2012;22(9):1147–62 .

- Bode L, et al. Science 2020;367:6482 .

- Azad MB, et al. J Nutr 2018;148:1733–42 .

- McGuire MK, et al. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;105:1086–100 .

- Harris JE, et al. Nature Metabolism 2020;2:678–87 .

- Holman RC, et al. Paeditr Perinat Epidemol 2006;20:498–506 .

- Donovan SM and Comstock SS. Ann Nutr Metab 2016;432:62–70 .

- Marriage BJ, et al. JPGN 2015;61(6):649–58 .

- Berger B, et al. Eur J Pediatr 175:1505 .

- Goehring KC, et al. J Nutr 2016;146:2559–66 .

- Puccio G, et al. JPGN 2017;64(4)524–631 .

- Nowak-Wegrzn A, et al. Nutrients 2019;11:1447 .

Are you a Healthcare Professional?

Important Notice and Declaration

Breast milk is best for babies. Professional advice should be followed before using an infant formula. Introducing partial bottle feeding could negatively affect breast feeding. Good maternal nutrition is important for breast feeding and reversing a decision not to breast feed may be difficult. Infant formula should always be used as directed. Proper use of an infant formula is important to the health of the infant. Social and financial implications should be considered when selecting a method of feeding.

The information provided on this website is intended for use by healthcare professionals only. It is a condition of use of this site that you are a healthcare professional within the meaning of regulations within your country of practice. Then denoting below Yes I am/No icons. For Healthcare Professionals based in Australia : It is a condition of use of this site that you are a healthcare professional within the meaning of the Marketing in Australia of Infant Formulas (MAIF) Agreement or the Therapeutic Goods Act.